Loe de Jong’s Conscience

Gerton van Boom, Uitgeverij Verbum, 25th April 2008

In 2004 we started with the publication of the Verbum Holocaust Bibliotheek (Verbum Holocaust Library) series. In the fourteen years since, Verbum publishers have been searching high and wide for new or untranslated books that are worth publishing. The focus was always on ‘new’ or ‘untranslated’. The ongoing search has also produced a large library. A knowledge of the broader terrain is necessary for such a journey, as the landscape, though not endless, is vast and difficult to survey.

A criticism that one often hears is that so much has already been published, surely by now all has been uncovered and put to paper? True, much has been published, a great amount, but I am convinced that all is not yet known and that the picture painted by history is not complete. Our viewpoint changes with, and through, time. In a hundred years the Holocaust will probably be looked at in a different light, giving other (more definitive?) answers to the question of how it was possible that the Holocaust could have happened. For instance, there is already a shift away from Raul Hilberg’s image of the perpetrator, towards a much broader inclusion of perpetrators than just the Nazi’s and their accomplices. In light of which, Verbum Publishers have purchased two new German volumes by the historians Götz Aly and Christian Gerlach. And here I would like to broach another point: the great mountain of writing which is still increasing in volume. Whilst contemplating the amount of work already published and at the same time searching for new works, the realization came that many good and important books had not been re-published for a long time. They may still be found in a library somewhere or perhaps purchased second-hand, but they are nearly out of the reach of new generations. It is often assumed that not re-publishing an existing book means that it has therefore lost its importance. Which of course is not the case. Or at least, not always.

Uitgeverij Verbum Publishers have therefore decided to re-launch and up-date certain volumes, and to showcase them again in a new presentation. The first of these is Bettine Siertsema’s volume: Eerste Nederlandse getuigenissen van de Holocaust, 1945-1946 (First Dutch Testimonies of the Holocaust**); Verbum, Hilversum 2018. It presents again in book form, ten of the first witness accounts of the persecution of the Jews, with an authoritative introduction explaining why these titles were chosen.

More publications in this section are to follow. In Depot (In Custody**) by Philips Mechanicus is another example of a book that must not go out of publication. In co-operation with Herinneringscentrum Kamp Westerbork (Camp Westerbork Memorial Centre), it too has been given a fresh presentation and the spelling has been modernised.

We need not worry about Anne Frank and Etty Hillesum’s books, as their continuing, immense popularity will ensure that they will always find their way to readers, now and in the future. The echelon of lesser-known authors, however unfairly, have difficulty in sustaining media attention, if indeed any attention was paid in the first place. Consider the diaries of David Koker. They have been re-published but the annotated, academic volume in English simply fails to reach publication in the Netherlands. Books also deserving of renewed attention are those by Hans Wielek, Sam de Wolff, Eddy de Wind and E.A. Cohen, to name but a few. Interest in these books is receding due to lack of attention from publishers; and, yes, it can be argued that the above selection is based more on historical importance than commercial considerations. Generally, Anne Frank, Etty Hillesum, Philip Mechanicus and David Koker (my list is incomplete) are attested greater literary qualities, but from a historiographic point of view the other first-generation authors carry the same importance.

*

The above only deals with part of the literature on the Holocaust; the autobiographies, recollections and memoires. But what about professional historical writing in the Netherlands? Something on which I have already commented in an earlier essay. After Loe de Jong, professional historical writing changed direction. Following on from the comprehensive works (Abel J. Herzberg, Jacques Presser and Loe de Jong), the established form of historical writing evolved into voluminous works dealing only with separate sections. Each one being necessary, useful and interesting. Yet they do not appeal to the broader public, who are reluctant to immerse themselves in 600 pages of detailed academic study on the role of the notary in the Shoah in the Netherlands (Raymund Schutz, Kille mist (Cold mist**)), or in the 1050 pages of scholarly comparison of the Netherlands, Belgium and France (Pim Griffioen & Ron Zeller, Jodenvervolging in Nederland, Frankrijk en België (Persecution of Jews in The Netherlands, France and Belgium**)). Both good, thorough and important studies, but not to the taste of the broader public. One of the few academically sound books which did reach the broader public was the study by Bart van der Boom (‘Wij weten niets van hun lot.’ Gewone Nederlanders en de Holocaust (“We know nothing of their Fate.” Ordinary Dutch People and the Holocaust**)), but the book was controversial.

Following Loe de Jong, a new comprehensive Dutch work was never written. Loe de Jong published his final pages on the persecution of the Jews in 1988 in Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog (The Kingdom of The Netherlands during the Second World War**), a book which he had started to write in 1967. As already stated, no Dutch historian has ventured to write a comprehensive overall view of the persecution of the Jews in the Netherlands since that publication. No-one dared to challenge or better the great historian, nobody dared to even to think of trying. In recent weeks Katja Happe’s book has been published, Veel valse hoop. De Jodenvervolging in Nederland 1940-1945 (Much False Hope. The Persecution of Jews in the Netherlands 1940-1945**), it qualifies as a comprehensive study, but she is German. The last comprehensive study before that was by the Englishman Bob Moore (Victims and Survivors: The Nazi Persecution of the Jews in the Netherlands 1940-1945) and published in 1997. So, the two most recent, comprehensive studies on the persecution of the Jews in the Netherlands were both written by foreigners. They dared to do so. But is it a matter of daring?

On reflection, how many people have even read Loe de Jong’s Het Koninkrijk from cover to cover? Who is able to visualize an overall picture of his image of the history of the persecution of the Jews. He left us a great and extensive legacy, but is it accessible in a practical sense? To coincide with the current planned revival of important diaries and memoires, Uitgeverij Verbum Publishers put to the NIOD the idea of gathering together the relevant passages on the persecution of Jews from Het Koninkrijk and making them available in a manageable format. In answer to my initial e-mail, of 8th April 2016, concerning this, Wiechert ten Have (NIOD interim-director) immediately returned the following mail:

‘That idea is certainly of interest. You have come to the right address. I shall have to put it to our own specialists in this field. My immediate thoughts are that the texts are, naturally, out-dated here and there in an academic sense. Of course, they are informative and part of a monumental heritage! A good introduction would therefore indeed be necessary. Possibly also a commentary.’

Thus, a project was born. Frank van Vree, Wiechert ten Have’s successor, also showed his interest in the project. Before we could start, I approached Loe de Jong’s family for their permission, and they too were in favour of the selection being re-published. Time to get started then!

Roughly two years on, the two volumes of Jodenvervolging in Nederland, 1940-1945 (The Persecution of Jews in The Netherlands, 1940-1945**) are ready, though it must be said in all honesty that it was a large and very difficult project. I shall spare you the details of the practical problems we needed to overcome. One of the biggest obstacles was the sheer volume of the work. It is more than 2750 pages long. Verbum have never before published such a large book. An earlier, similarly megalomaniac project (at least for a publisher the size of Verbum), was the translation of the magnum opus of Raul Hilberg, the founder of Holocaust historiography, who is still considered an authority to be read and studied today, and who will still be relevant for some time to come. The Destruction of the European Jews by Raul Hilberg numbers about 1550 pages and covers three volumes. Lou de Jong has nearly double that number of pages! (… our backs are still sore.)

In many other ways Loe de Jong’s work (kept for so long inside Het Koninkrijk) is similar to that of Hilberg. It was (is?) a trendsetter, sets the tone and is yet unsurpassed. These are of course big claims, and some scholars may beg to differ, but I stand by them. Yet I shall refrain here from an analysis of the similarities between Loe de Jong and Raul Hilberg and allow myself only to state that Loe de Jong was well acquainted with Hilberg’s work. Hilberg was one of the few historians in the matter of the Holocaust whom Loe de Jong appreciated, cited and read intensively. So, in the Dutch context the two have a connection and therefore it was only logical for us to offer both of them a place under the same publisher’s roof, in spite of the fact that Verbum really does not have enough staff to handle such large projects.

*

In Het Koninkrijk it was not Loe de Jong’s intention to write a separate work on the persecution of the Jews, but his analysis and account of it were an integral part of the broader story of the Netherlands during the Second World War. Therefore, in his handling of the persecution of the Jews, Loe de Jong does not present us with an in-depth analysis of the origins and underlying causes of the Shoah. As a separate work it would have been a different kind of book, although I am convinced that both his motivation and verdict would have been the same. It had always been Loe de Jong’s wish to publish a separate book on the subject, and it is unfortunate that it did not happen sooner.

We can read the following concerning his motivation on page 2452 (chapter 19, ‘Hulp aan Joodse vluchtelingen’ (Aid for Jewish refugees**) – Yes, we may as well get used to the new referencing and annotation as well…)

“I was thinking too much about the ultimate victory, and not enough about the Jews, that is what I feel now”

I did not feel or express enough solidarity with those Jews, that is what I feel now”

Loe de Jong’s conscience thus made the matter a very heavy weight for him to bear. Also of course because he himself had lost many close family members, including his parents and his twin brother Sally.

Yet a heavy conscience is only one aspect. The other is his verdict. The perpetrators and those ultimately responsible, were of course the Germans (or rather the Nazi’s), but the ‘protagonist’, every story has one, was not a Nazi (who were mostly instrumental, at times inherently fanatically perverse) but a Dutch Jew, David Cohen, the chairman of the Jewish Council. Loe de Jong’s reaction to the assistant chairman of the Jewish Council, Abraham Asscher, was as a rule less fierce and less disapproving.

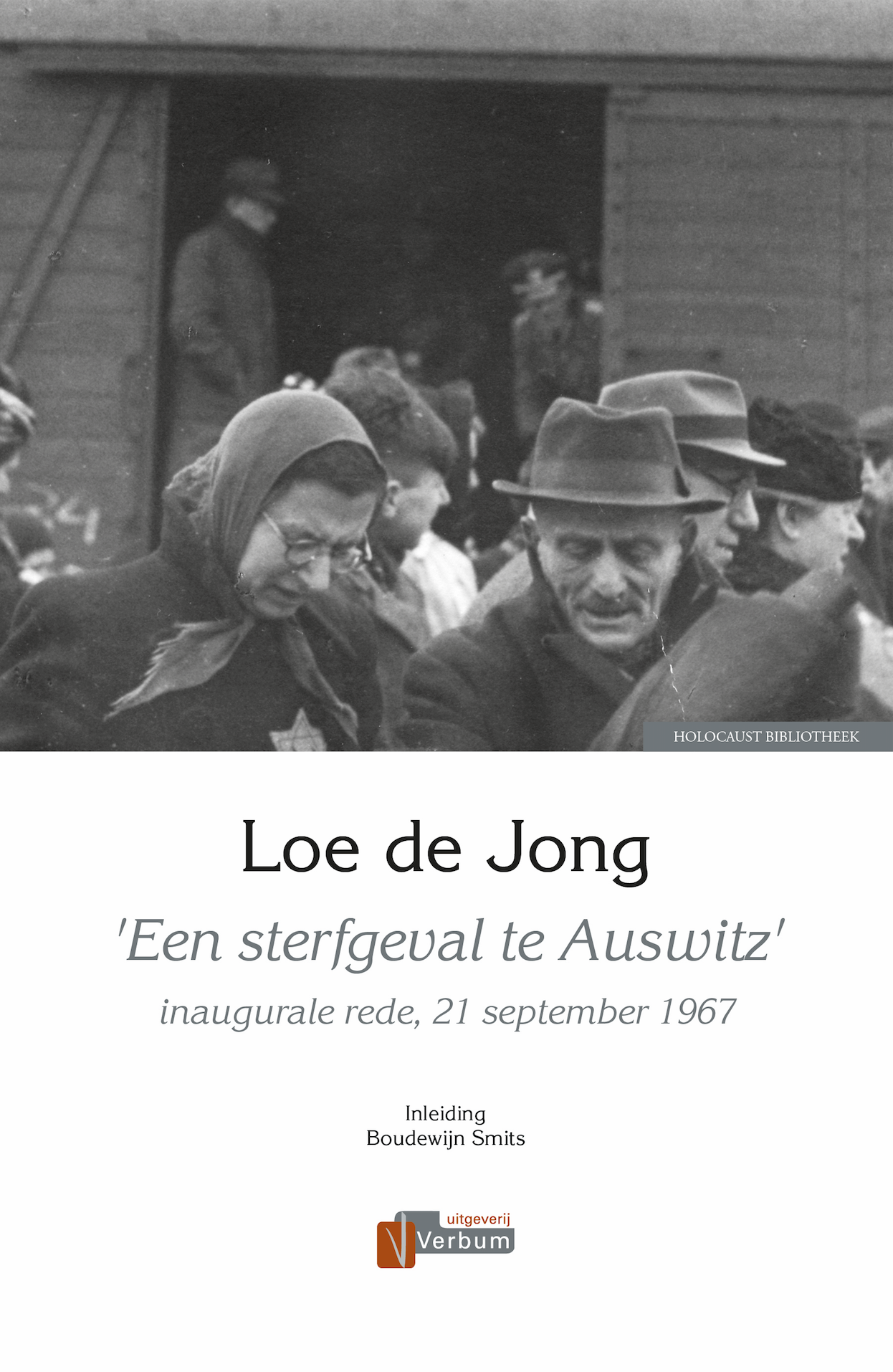

In his inaugural speech on 21st September 1967 *, Loe de Jong names David Cohen in the very first sentence. He was very angry with Cohen and the Jewish Council.

*Een sterfgeval te Auswitz (A death in Auswitz**) – complete with an authoritative commentary by Boudewijn J. Smits – ‘Loe de Jong’s loodzware thema’ (Loe de Jong’s leaden theme**) – this booklet was re-published by Verbum to accompany Jodenvervolging in Nederland (Persecution of Jews in The Netherlands**)

‘Whatever one has been told or learned about the Jewish Council’s policy, it strengthened the image of the servile, subservient, cowardly Jew.’ (page 1314, chapter 12, ‘Laatste fase van de Jodenvervolging’- Last phase of the Persecution of the Jews**) Elaborately and meticulously, Loe de Jong lays bare what proved to be (on hindsight) the disastrous work of the Jewish Council. Cohen and cohort believed in the biblical proverb taken from Ecclesiastes, cited by Engelandvaarder* R.A. Levisson: ‘A living dog is better than a dead lion.’ (page 2009, chapter 16, ‘Gedeporteerde Joden’ (Deported Jews**)) Such was the Jewish Council’s policy: compliance and docility in order to avoid something more terrible, in the expectation (or hope) that the war would soon come to an end. But that policy had devastating results. To begin with, it destroyed the solidarity between those inside and outside the group. On the inside: by trying to protect a certain select group of Jewish Council members from deportation, the poor Jews who did not have any vitamin ‘C’ (contacts) were left with even less chance of survival. Cohen spoke of holding on to the most important people for as long as possible (Loe de Jong, ‘Een sterfgeval te Auswitz’, p. 31). On the outside: because it displayed to the outside world a seeming acceptance by the Jews themselves. Why should we, who are not Jewish, help the Jews if they themselves are compliant, and instrumental to cooperation in their own exclusion? ‘During 1941, the passivity within Jewish circles helped to encourage the passivity of those who were not Jewish.’ That was the reasoning (page 1259, chapter 11, ‘Deportaties, derde fase (Deportation, third phase**).

*Engelandvaarder = escapee to England during the Second World War

In addition, the cooperation of the Jewish Council seriously thwarted any feelings of self-respect. Better a dog alive than a lion dead? For centuries that had been the attitude of the ghetto Jews, and antisemitism has never been able to banish it successfully, it has rather reinforced it. The real hero in Loe de Jong’s analysis is L.E. Visser LL.M., the Jewish chairman of the High Council, whom after being ousted from his position (with absolutely no support from his co – members) called for conscientious Jewish non-cooperation with the Nazi’s, arguing that cooperation could only lead to losing everything, including self-respect. He was convinced that solace would only be found through an attitude of conscientious non-collaboration. He opposed Cohen and the Jewish Council but his was a voice crying in the wilderness. He could see through the Nazi’s dirty politics of divide and rule, but there were many who hoped at least to be able to save their own skins in that treacherous game, those who were well-off, privileged and protegees to the board of the Jewish Council in the lead. Loe de Jong speaks of an ‘armed truce’ between Cohen and Visser. Loe de Jong: ‘…, the conviction that The Jewish Council was sliding steadily further into subservience to the occupier became more and more apparent, a servility that was, according to Visser, completely contrary to the dignity that Jews should possess.’ (page 589, chapter 7, ‘Naar het getto’ (To the Ghetto**))

Cohen’s policy made it quite simply ‘each man for himself ‘. Looking back, we can see where this led. Loe de Jong was thoroughly aware of the fact that the downfall of the Jewish population would probably have occurred without this collaboration, but without it at least there would have been self-respect and a tiny chance of solidarity from the rest of the Dutch population.

*

A second sting in the tail of Loe de Jong’s analysis of the Persecution of Jews concerns the attitude of Dutch officialdom. On page 881-882 (chapter 9, ‘Deportaties, eerste fase’ (Deportation, first phase**)) he writes: ‘As far as the eventual protection of the Jews was concerned, or even a small step in that direction, the Dutch government, particularly, displayed a total absence of any action.’ ‘Where on earth in this bureaucratic mess can one find a man with guts?’ ‘There aren’t any.’ ‘Koos Vorrink’s words on the aid for deported Jews.’ Report from the Pakkettencommissie (Parcel Commission), 1947: ‘A shortage of initiative, daring and imagination and an overabundance of formality and bureaucracy.’ Loe de Jong speaks of ‘punctuality with damaging effects’. Also: ‘questionable formalisme’. ‘When a person suspects that the government they serve is immoral, they will not want to keep looking for proof that those suspicions are justified.’ (page 2208, chapter 17, ‘Terugblik’ (Retrospection**)) The ‘London’ policy regarding the Jewish refugees was ‘inhuman’; and many more quotes to that effect …

It is not surprising then that the cream of the civil service, and the secretary-generals headed by Frederiks, are not spared in the least. Again, and again, the same picture emerges: cooperation in order to avoid something more terrible. Yet it did not work out that way at all. The civil servants either did not or would not see that working with the Nazi’s (collaborating) meant death to the Jews. Loe de Jong did not put it into writing, but you can just hear him thinking that the Dutch civil service offered up the Jews to the bloodthirsty wolves, in the hope that they themselves would be spared. The Jews were collateral damage, an indirect and accidental loss.

This leads us to conclude with Loe de Jong that the Persecution of the Jews was the result of a gross lack of solidarity on many different levels, both personal and official, even from within the varied Jewish community itself. That is the unequivocal truth, and the most important lessons to be learned from the Holocaust should be based upon it. This is what needs to be legally embedded into a new Landoorlogregelement (Land Warfare Regulations), equipped with adequate penalties. This is the lesson that should be conscientiously hammered home in our schools, year in year out. Showing solidarity must be rewarded and honoured, and not showing solidarity must carry a penalty. This must become the practical result of ‘Nooit Meer Auschwitz’ (Auschwitz, Never Again); the Dutch Auschwitz Committee and all other commemorative bodies, boards of Holocaust museums and memorial centres should preach it year after year. This is not literally what Loe de Jong wrote; it can only be distilled out from between the lines; this is the private conviction of the author of this essay. Of course, it is not the conclusion of a professional historian who reasons and examines abstractly, with little emotion. It is after all not a conclusion, but a recommendation, and is the terrain of politicians, not of historians. Best of all would be for officials and teachers to embrace this policy fully and voluntarily and interweave it into their day to day policies and actions.

*

This brings me to my final comment. Books on the Holocaust can be divided roughly into three categories: books that 1) describe events, 2) explain events or 3) engender outrage about events. And of course, many books are a mixture. De Jodenvervolging in Nederland by Loe de Jong is mainly a description of events, but here and there it is gives explanations and the author is suitably, but clearly outraged. A mixture of 1), 2) and 3) therefore. Most books, especially the memoires, autobiographies and recollections are such mixtures, mostly of 1) and 3). Few books fall only into category 2), and neither does that of Loe de Jong. It is also unlikely to have been his aim. Although less so than with Presser (Ondergang), the Persecution of the Jews and how the (Jewish and non-Jewish) community had reacted were a raw nerve, which had to be treated with academic distance and care. But it was not an easy task.

More recently we have also had the controversy concerning the Nederlandse Spoorwegen (Dutch National Railways). Salo Muller, a survivor of the Holocaust, claims that the money used to pay the NS by the Nazi’s was stolen from citizens, including from his parents. In other words, the Jews who went to the gas chambers paid for their own train ticket. That is such a gross injustice that the former Ajax physiotherapist decided to take action against the NS and demand that they refund the money. During the war the NS was state owned and collaborated fully with the Nazi’s. No explicit questions were asked as to where these Jews were being deported and why nobody sold them return tickets. How did the NS react to Salo Muller: a nutmeg, an elbow thrust, a headbutt and they were rid of Salo Muller! The NS do not award damages. Neither do they apologise or do penance, nor do they accept blame. Of course, they find it all very regrettable. The director of the NS, Roger van Boxtel wants to ensure that his company never forgets its role during the war. So: the NS will sponsor the National Holocaust Museum. That in itself is a good thing, but it shows that Roger van Boxtel has no real understanding of the issue. There should have been a mea culpa, a publicly declared deep regret, and compensation for the few surviving relatives. Sponsoring the National Holocaust Museum in addition would then have been acceptable. Yet the age-old reflex of Government, against which Loe de Jong rebelled with ill-concealed disgust, has still not changed, even now.

What makes it even worse is that Emile Schrijver, the director of the Jewish Cultural Quarter which is part of the National Holocaust Museum, allowed himself to be quoted in NRC Handelsblad, 3 April 2018: ‘Emile Schrijver, …, finds it “unbefitting, to continue applying merely the ethics of right and wrong when looking at the role played by the NS”.’ In other words, it is no longer appropriate to criticise the policy of the NS during the war. Is there an analogy here with the actions of the Jewish Council during the war? Is it a case of divide and rule? Ignoring one group altogether, while handing out money to another group in the hope of clearing your guilty conscience? I fear that the NS has not yet heard the last of Salo Muller. And I fiercely hope that Schrijver has been either misquoted or badly quoted …. I hope that he has also demanded satisfaction for the remaining relatives from the board of the NS. Yes, it is fine if he works with the NS and accepts their sponsorship, it is to be welcomed even, but putting ethical standards aside in regard of the Shoah, never! That is the message that can again be read in Loe de Jong’s, now more accessible, new (or old?) book.

** title translation of untranslated books